This essay contains full spoilers for Neon Genesis Evangelion (anime and manga), End of Evangelion, Rebuild of Evangelion and Evangelion: Anima. It also contains frank descriptions of suicide and suicidal ideation.

Evangelion is over. Again. Nearly fifteen years since the first release in the Rebuild, and nine years since the previous entry, the bafflingly titled “Evangelion: 3.0+1.01 Thrice Upon a Time” has finally been released. To prepare for this, I marathoned the original TV show, End of Evangelion and the Rebuild series- and of course, I was still unready. Not only is it one of the longest animated films ever made, but its themes, presentation and overall tone feel shockingly different from previous Evangelion media (consider that your last warning if you’ve yet to see it). As such, I can’t possibly review it, at least not yet. Indeed, any ranking is going to be poisoned by recency bias. Hours of mecha melodrama rattling round in my brain, I return to a specific line- one both spoken in and used as a tagline for End of Evangelion:

“The fate of destruction is the joy of rebirth.”

Evangelion is a franchise of many rebirths, with End of Evangelion most obviously seeking to provide a proper ending to the TV show. Still, even before that, the three significant tone shifts in those original 26 episodes are all part of the one thing we call “Neon Genesis Evangelion.” Shinji begins the series as the reluctant pilot of Eva Unit-01, isolated and seeking any reassurance or praise from his father. He keeps himself at a distance from others, with Ritsuko citing the Schopenhauer metaphor of the “hedgehog’s dilemma” to his would-be handler, Misato. Shinji yearns for a mother, but Misato fails to fill that role, not for lack of trying. Instead, his connections with his classmates, Kensuke and Toji, and then later his fellow pilots, Asuka and Rei, allow Shinji to come out of his shell. This arc fits the more standard mecha “monster of the week” formula, often derisively compared to Nadia’s infamous island arc. I don’t think this is particularly fair, as it’s not only more entertaining and varied than milling about on an island, but it’s also essential in developing the cast beyond their various neuroses.

And then.

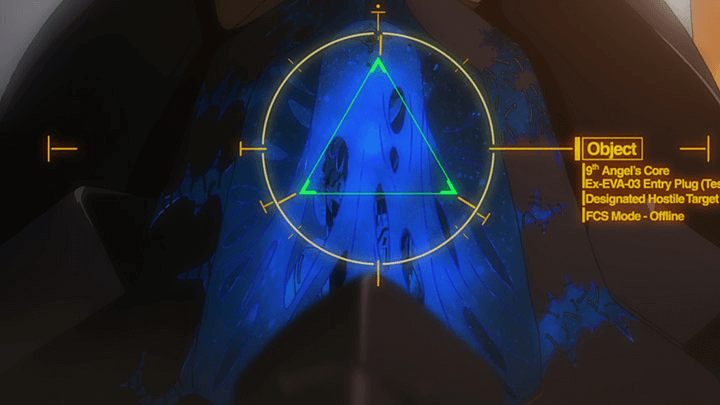

With the arrival of Unit-03, possessed by the thirteenth Angel, Bardiel, Shinji is dealt a crushing betrayal. Shinji is unwilling to fight, fearing that he will kill the pilot inside, so Gendo intervenes, allowing the experimental Dummy Plug system to control Unit-01, viciously tearing apart the Eva/Angel with what to Shinji feels like his own hands. Upon Misato finally telling him the truth, that Toji was the pilot, he breaks down, threatening to destroy NERV and later choosing to run away from Tokyo-3 altogether. Thus the narrative enters its final phase- though Shinji does, of course, have to pilot the Eva again, his betrayed trust from both his father and Misato leave him isolated within his mind. It would be easy to divide the show into “sad/happy/sad”, but the Shinji of the final episodes displays an intensity of emotion far removed from his starting point. As a series so preoccupied with introspection, when Shinji’s mind changes, so does the tone of the entire show. How much the staff planned this is up for debate- the original ending is mesmerising and rushed in equal measure. Episode 25, in particular, has almost no original animation. Thus, it underwent its fourth metamorphosis- the darkest chapter of the entire franchise, End of Evangelion.

It’s tempting to try and read into Anno’s psyche with each of his releases- a new Evangelion movie doesn’t come around often, and Anno is quite private and indirect. The viewer becomes an armchair psychologist with his works full of psychological terms, sifting the guts like an anime augury. Such desires arise from auteur theory, and considering the army of staff surrounding Anno, I’m wary of how personal the connections we make are. Bearing these reservations in mind, it’s clear that both the toll of the production and reception to the original series was detrimental to Anno’s mental health. Supposed fans sent hundreds of death threats to the studio, which appear in End of Evangelion. It’s not just the tone that’s dark, but the visuals too- even the dayglo Evas appear muted and cold. Horror was always a part of the original series, but EoE has some of the bleakest imagery seen in an animated film. Those not content with the monologues of final episodes get the spectacular finale they wanted, and it only cost the destruction of every character.

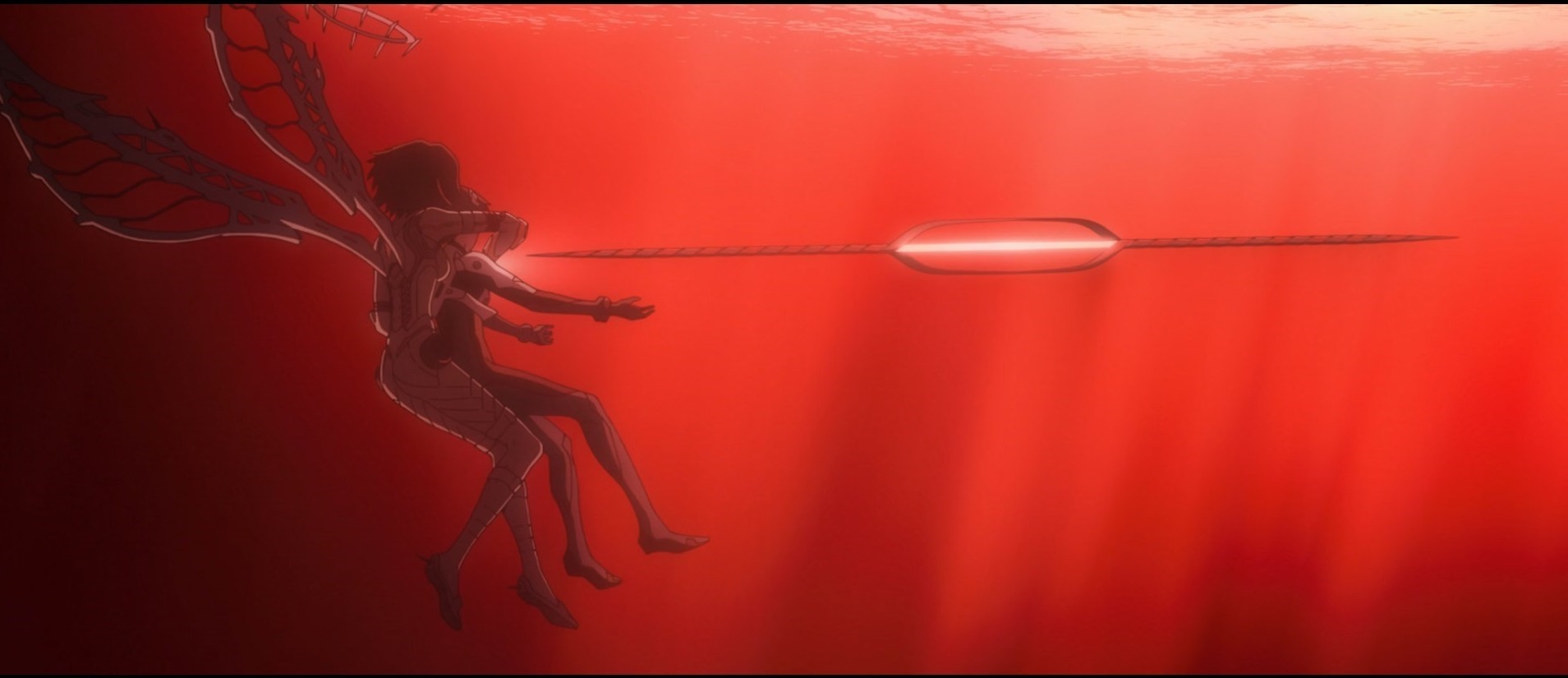

Lilith/Rei dissolves all humans into their primordial LCL, scored to “Komm, süsser Tod” (Come, Sweet Death) and the screams of a dying planet. It is but the violent crescendo to a relentlessly bleak film, one that borders on cruel. A broken Shinji masturbates to a comatose Asuka. Maya receives reciprocation from Ritsuko, though it is Rei taking her form, hugging her into oblivion. Rei, a character so beloved by Japan that Anno described them as a “nation of children”, becomes both horrifying death god and object of intense body horror, her gigantic head falling twisting flesh and bone as it falls into the red sea. The Mass Production Evas do not just defeat Asuka; they pull her apart, devour her as carrion. Misato succumbs to gunshot wounds before the JSDF blow her apart. It presents the same hope that the original did- through the reversal of Human Instrumentality, each human soul can reclaim their individuality, but tempered by Shinji using said freedom to strangle Asuka. Whether Anno did this out of “revenge” is irrelevant, but the dark is made definitive in this remaking. Without the backlash, the series could have ended with “Congratulations” rather than “Disgusting/I feel sick.” Nevertheless, what we have is gorgeous, horrifying, strange and compelling in equal measures, a fitting end to one of anime’s most iconoclastic series.

Except, oops, now it’s one of the most influential anime of all time, a merchandising empire, and perhaps even responsible for internationalising otaku culture. The End of Evangelion finished the story, but the franchise continued in every medium other than animation. It was the first mecha series where the character merchandise dramatically outsold the model kits and action figures, inspiring dating sims, cosplay and of course, over (number here) doujinshi. Oh, and that merchandising. While not quite to the apocalyptic scale of Pokemon, it’s entirely possible to live on Evangelion merchandise alone. The decade after End of Evangelion is not dissimilar from the period between Return of the Jedi and The Phantom Menace. Movies did not serve the newly created fanbase but instead a combination of comics, videogames and tie-in novels. The difference is that since the 1981 re-release of The Empire Strikes back, the original trilogy was not Episodes 1, 2, 3, but IV, V, and VI. There was the expectation of more. Star Wars also left the door open for eventual sequels, not just prequels, considering Return of the Jedi didn’t end with the cast all becoming one with the Force. There might not have been a good narrative reason for a continuation, but with Anno’s acrimonious split from Gainax, there was a monetary one. Having sued over millions in unpaid royalties, creating a new Evangelion underneath Anno’s new studio, Khara, made some sense. So, in 2006, after several years of behind the scenes production, a new tetralogy of Evangelion films were announced, dubbed Rebuild of Evangelion. Anno himself commented that he wanted to recreate Evangelion as he originally intended it to be from the beginning, now unshackled from technological and budgetary constraints. The actual aims of the Rebuild project were fuzzy, though. A simple remake of the original show? Something akin to the Star Wars special editions? Was it to be a sequel? Would it just be some soulless cash grab, a product to pander to a rabid fanbase?

Evangelion 1.11 doesn’t clarify any of those questions. It opens with a shot of red waves, mirroring the final moments of End of Evangelion. Ok, a sequel then. But then it is also a condensed beat for beat recreation of that first part of the original series, before the first major tonal shift. So, it’s a remake? No, but wait, product placement litters the setting. Misato still drinks Yebisu but can no longer offer it to Shinji because that would almost certainly anger the sponsors. There’s also an entire drawer filled with Doritos, which fansite EvaGeeks bafflingly describes as “not too gratuitous”, in case you were wondering about the state of the Evangelion Defence Force (the less cool EDF). For anyone squeamish about the fanservice in Evangelion (hardly unjustified given the age of Asuka and Rei), 1.11 decides to double down. Oh no. Was this the cash grab we all feared it would be?

Before this year, it had been a very long time since I’d watched it, as it is easily the most pointless of the films (the opening text even describes it as a prologue to the Rebuild project). Many scenes are shot for shot recreations of the original series, polished with higher budget animation and some occasionally dodgy CGI. Thankfully, said CGI is nowhere near as abhorrent as the Ghost in the Shell 2.0 edition, animes closest equivalent to the Star Wars home releases. It is nice to see some of the lesser Angel fights from the original expanded. Ramiel, everyone’s favourite octahedron, gets such an upgrade that they’re central to the movie’s climax, sporting fancy new sound design and being even closer to ripping off Super X from Future Police Urashiman. The fight itself is mostly the same, and that’s the running theme of 1.11: mostly the same, with some good, bad or weird changes.

There is no confusion between the identity of Lilith/Adam, and Misato takes Shinji to meet it much earlier than it happens in the original narrative. Misato is a lot less in the dark about the inner workings of Nerv, with her desire for revenge against the Angels outweighing any moral concerns. When Shinji runs away, he no longer hides out with Kensuke in his tent, which makes his eventual reveal in 3.0+1.01 somewhat clumsy and minimises the importance of his classmates in Shinji’s development. Rei has much more of a starring role, with the narrative climax greatly expanding on her part of protecting Shinji in the battle Ramiel. While it is nice to see her get more attention, I can’t help but feel that has more to do with the development of “waifu” culture, the endless arguments about “best girl” and merchandising opportunities than any artistic desire to do her justice. None of the other characters gets this kind of special treatment, relying on you already understanding their archetypes to distinguish them. Perhaps Anno has softened on his position that the popularity of Rei is to do with Japanese people being unable to deal with strong women, or maybe he just wants to give the fans what they want.

I shouldn’t complain since all that and more applies to Asuka in 2.22, who even gets a special prototype plugsuit to show her ass off directly to the camera. She’s where the purpose of the Rebuild project gets even more muddled. She carries a doll in several scenes, referring to her mother’s doll from the original series. The doll is a convenient shorthand for her traumatic backstory if you’re a fan, but it means absolutely nothing to someone who had watched Rebuild alone. Even by the second entry, it had given up on being an entry point for new fans, with the number of divergences and subversions effectively crossing off the question of it being a remake. As someone who has spent far too much of my life watching and rewatching the TV series, this makes 2.22 much more interesting, and I considered it an easy favourite in the series.

At least, that’s how I felt at the time. To start on a positive note, it has some of the humanity missing from the first film. A scene where Shinji and his classmates go on a trip to an aquarium offers rare breathing room in an otherwise breakneck-paced storyline, offering interactions even the original series lacked. It also helps to flesh out the setting, one that is in some ways grimmer than the original. While the old teacher (the same one plastered all over EvaGeeks) exposited on the state of the world post Second Impact, we didn’t get to see that world. Here we see the dead seas, which is what makes these giant research aquariums necessary. Rebuild attempts to broaden the scope away from just Japan, with locales varying from Russia, France and, uh, the moon. There’s also the Vatican Treaty, a mandate from the UN that limits each country to three active Eva Units at a time, both increasing the scope and making the organisation feel more consequential than they did in the original. If mecha action is what you want, here it’s plentiful and often spectacular, a decent sweet spot between this and the more incomprehensible choreography of 3.33 and some of 3.0+1.01. And yet, this second entry is where Rebuild becomes unsure of what it wants to be.

To even say the name “Mari” is like throwing a piece of meat to the starved dogs of the Evangelion fandom, and yet she’s key to understanding some of the fundamental flaws of Rebuild. Mari Illustrious Makinami, the only brand new character of any significance, was supposedly implemented to “destroy Evangelion”- make a clean break into something new. Indeed, there isn’t a character in the setting quite like her, and by hijacking Unit-02, she allows huge divergences to occur. Unfortunately, this radical character is a British schoolgirl with glasses who enters the story proper by landing crotch first into Shinji, conveniently tearing her stockings before sniffing him. Maybe it sounds prudish, but it would have been better for this arbiter of change to be a bit more than just a collection of otaku fetishes. The staff even contemplated giving her animal tattoos to one-up the iconic designs of Asuka and Rei (I suppose its restraint that’s only seen naked in the final film, finally disconfirming this). Animation is a visual medium, but there needs to be at least something behind said visuals. The refrain from defenders of Mari had always been that we just hadn’t yet seen her backstory, uncovered her secrets. Now the series is over, and we can conclude there was never anything there. Shinji does not even know her name over an hour into the final film. She is the positive, energetic “genki” type, singer of songs and very little else.

Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Evangelion character designer and certified cat lover, elaborated on the Showa era songs she sings in his manga adaptation. The manga itself is outside the scope of this article, taking almost twenty years to finish and diverging more and more from the traditional canon as it went on (not unlike Rebuild). But, in a non-canon bonus chapter, Mari is classmates with Yui and Gendo at university, her not ageing since then thanks to the ever nebulous “Curse of Eva”. It’s a nice bit of fluff, explaining away her interest in Showa music from having been alive in that era, if not her overall lack of maturity in the present day. Sadamoto admitted Khara provided him with no guidance on this. He merely added it as a fun aside, yet 3.0+1.01 incorporates this backstory out of inertia. If this doesn’t show how little consideration the team gave to Mari and how hands-off Anno was with some parts of Rebuild, I don’t know what does. Mamoru Oshii, of Angel’s Egg and Patlabor fame, commented that “Hideaki Anno is more of a producer than a director these days”, noting that Anno cares more about the commercial side of anime than he does. Indeed, part of the goal of Rebuild was to rejuvenate the anime industry as a whole- so he aimed to court the demographics he saw as leaving anime behind. What better way to draw back the otaku who had aged out of Evangelion than by reigniting the waifu wars with fresh blood? Perhaps this also explains one of the other significant changes from the original to Rebuild- the titular Evangelions.

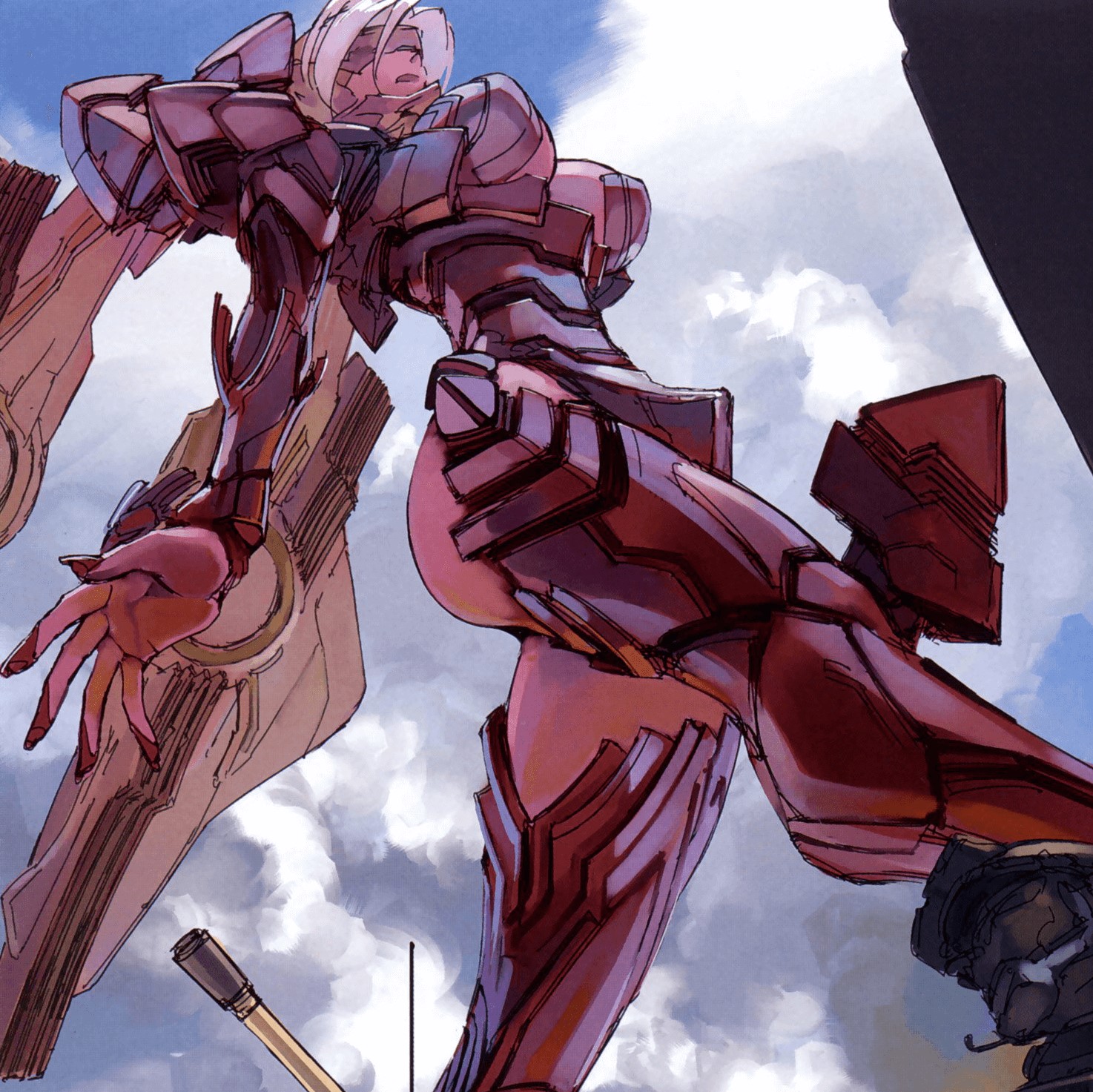

Eva Units in Rebuild may resemble their original counterparts, but their presentation is entirely different. To put it simply, they are no longer horrifying. Sleeker, lankier and with the utmost care in hiding the human frame under the armour, resembling their model kit counterparts far closer than the original designs ever could, thus making far more merchandising possible. Anno originally wanted the Evangelions to be as challenging to reproduce in toy form as possible, annoyed by how meddling these companies could be. He wasn’t wrong to be worried about that- while the clown colours of the RX-78 Gundam are now iconic, it wasn’t what Tomino had in mind. Sunrise ordered the change from a greyish white to appease the sponsors, including Clover, who initially held the license for Gundam toys. Clover is the same company that would ultimately cut the series short. So naturally, Rebuild inflates the number of Eva units while also making them more similar to one another, allowing action figures and kits to be more easily produced. So reveals the primary purpose of the Vatican Treaty to allow the existence of more Eva Units without ever having to animate more than three at once. The more obnoxious fans of Evangelion protest at its inclusion in the mecha genre, partly because of general snobbery, but more specifically, the refrain of “ACTUALLY they’re not robots, so it can’t be a mecha show”. Such arguments belie a simple ignorance of the genre- the word “biomechanical” exists for a reason. They aren’t even the first to have some kind of a-ha dark twist about them. Like much of NGE, it’s not that they’re incredibly original, but that they excel in their execution. Their jaws unlocked and screaming, crawling across the ground like overgrown apes, cruel mockeries of the human form. They’re part of what captivated audiences in the first place, the dichotomy between their kitschy super-robot designs and nightmarish behaviour propelling more of the plot than those fans above would like to admit. As with so many other modern mecha properties, Rebuild uses CGI extensively to depict the Evas. While it does mean we avoid some of the weirder off-model moments from the original, this can work to its detriment. There’s little to distinguish them from any other super robot, and while inflated budgets allow them to sprint and pirouette, they feel weightless. Unfortunately, the worst example is when Unit 01 once again squares off against Unit 03. It is an event that changed the entire course of the original series. Here, it feels like a parody.

For starters, the pilot of Unit-03 is no longer a mystery to Shinji- he knows from the beginning that Asuka is in the Entry Plug, yet another subversion meant as a wink to fans. As in the original, Shinji refuses to fight, though this time out of absolute certainty that there is someone inside and that it’s a highly experienced Eva pilot who lives with him specifically to foster better camaraderie between the two. I’m not sure if this makes Nerv evil or stupid, but Gendo again engages the Dummy plug. The original makes much of Shinji feeling like he may have killed one of his best friends with his own hands while he helplessly watches. For some reason, in Rebuild, he cannot even see what is happening, with the Dummy plug obstructing his view entirely. What follows is the same fight, with subtle, strange changes. The battle is a lot bloodier, though Eva Unit-01 remains mainly unsullied. The bridge bunnies are still horrified, but the original portrayed this as literally sick-making. Perhaps with almost every Angel fight in Rebuild flooding the city with blood, both they and the audience have grown numb. That Unit-01 crushes Asuka’s Entry Plug in its mouth makes a more dramatic image but removes the connection to Shinji’s own hands. An ironic insert song has to do the emotional heavy lifting, which highlights the central issue: when Rebuild tries to redo, it will often look better but feel worse.

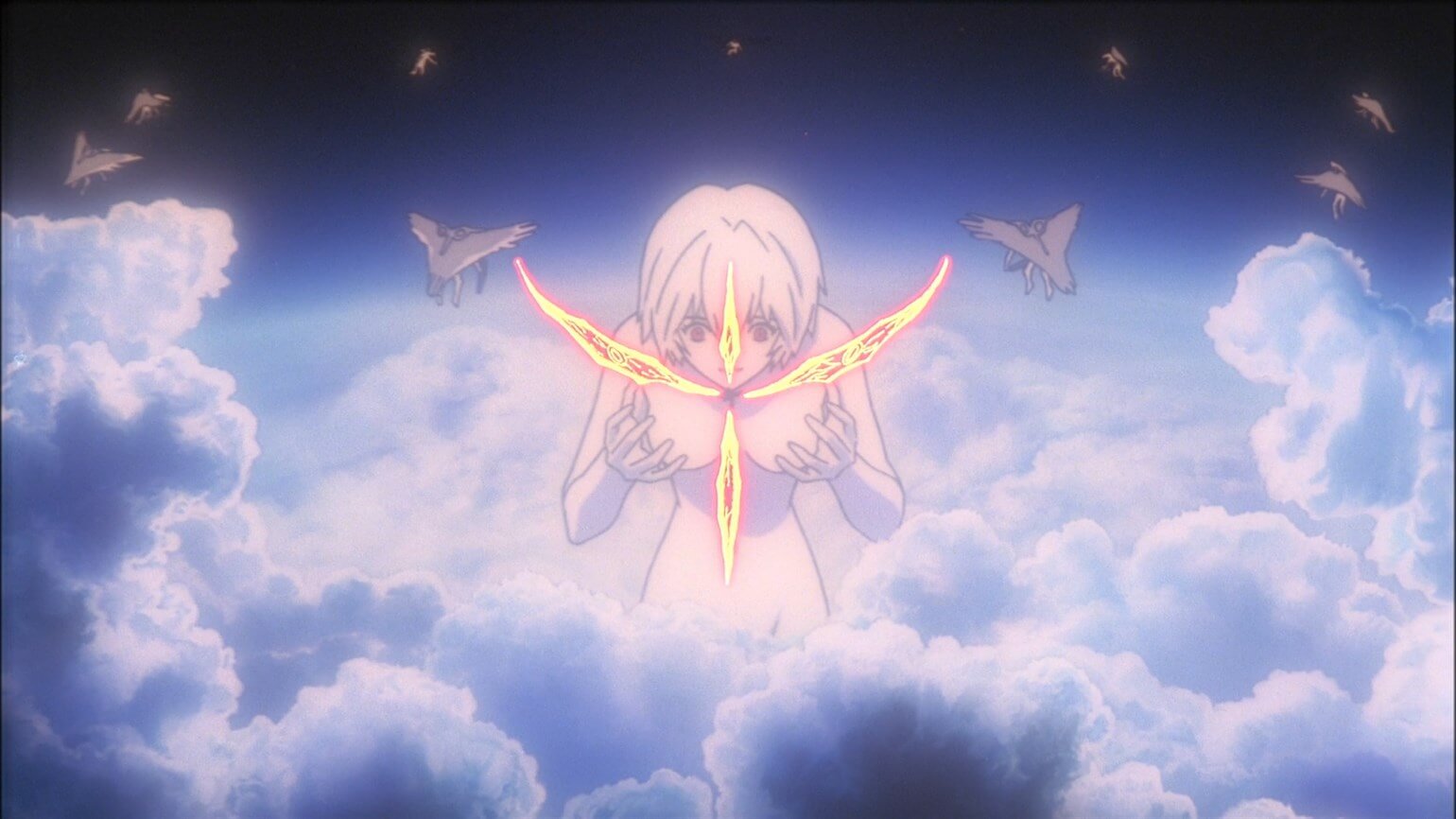

So the finale of 2.22 feels exhilarating. After much the same fight against Zeruel (albeit with Mari using berserk mode like some kind of videogame power-up), Shinji refuses to let Rei die, and in doing so, starts Third Impact far ahead of schedule. The scorched earth style break from tradition that Mari was supposed to embody comes from Shinji refusing to follow the script. His body breaking apart from the weight of fate, the music swelling, it’s hard not to get swept up. Interrupted by Kaworu in as yet unseen Eva Unit, he promises to make Shinji happy- this time. A cliffhanger that sent fans reelings, spurring all kinds of theories. Was this the same Kaworu from the original series? Why are there multiple Rei clones out and about in the preview for the third movie? We would have to wait three years (seven for a proper home release in the West) to find out.

Well, kind of. Evangelion 3.33 reframes the triumph of the previous ending with Shinji awaking 14 years in the future to a world trapped in the middle of an apocalypse. Easily the most controversial entry in the franchise and somehow the shortest at a lean 90 minutes, Rebuild has finally thrown away any pretence of adapting the original material. I’m still conflicted. The original series has a strained relationship with realism. The pirouetting Eva units of the previous films strained further, and by 3.33, all pretences have gone. Misato captains a Space Battleship Yamato reference with an Evangelion as a battery, surrounded by other floating battleships on weird laser puppet strings. Gendo’s new Nerv sends waves and waves of the new Nemesis Series, autonomous Eva units manufactured on an absurd scale. The basic but welcome attempts in 1.11 and 2.22 to make the world feel more lived have been obliterated in the apocalypse, replaced by endless grey structures that make the Geofront look conservative. I was angered when I first saw it; it felt disrespectful to a franchise I considered formative.

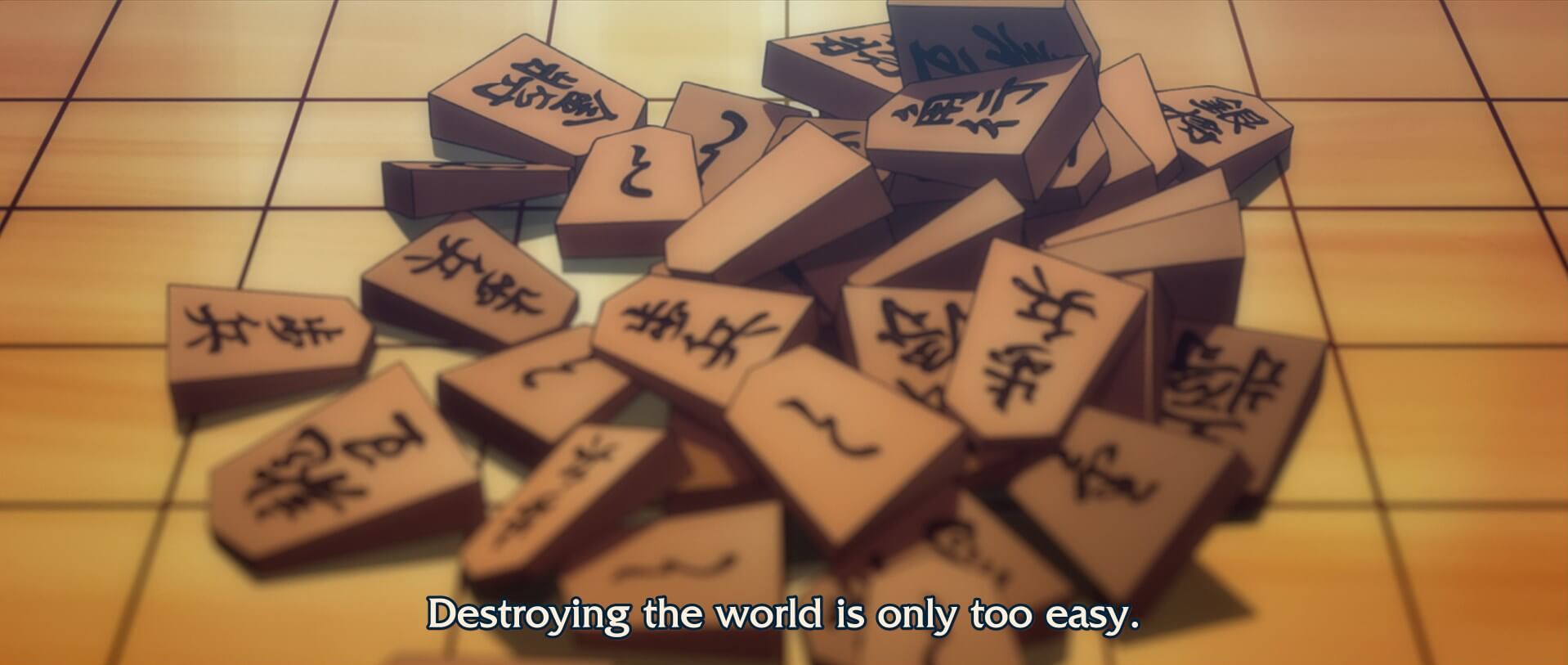

I’m far less precious about “franchises” these days, but I can’t pretend there aren’t decisions that still annoy me. The most common criticism of 3.33/Q is that the plot relies too much on convenience- if Misato explained the situation to Shinji, he would be less likely to repeat his mistakes. I think we can upgrade that criticism to “if anyone said anything of substance to anybody” because, as it stands, the job of exposition dumper falls to Fuyutski, a character who has even less to do in Rebuild than the original series. After Shinji leaves for Nerv (good thing they spent the intervening years redesigning the logo) with Rei Q (yet another clone with little to justify the new moniker other than acting as the “Quickening” for Shinji), he knows nothing. Nothing of this world, Misato’s new organisation Wille, or even why his dad has fancy new shades. About all that’s explained to him is his fancy new collar, the DSS (Deification Shutdown System, in case you were wondering) Choker, which will blow his head off should he decide to pilot an Eva. Misato, who initially cheered Shinji on in the finale of 2.22, can also manually detonate the collar should she so desire. This change in tune is left for the final movie to try and paper over, but for now, it just seems pointlessly cruel. Even with that, things somehow worsen for Shinji. The girl he thought he rescued is a hollow shell, like the returning Rei in the original series. Gendo, keen to turn up the dial on his “number one dad” schtick, walks away as Shinji screams at him to explain anything about what’s going on. It’s left to Fuyutsuki to clumsily fill in the gaps over a game of Shogi, and it’s here we get one of Rebuild’s most obvious metatextual moments:

I do have some sympathy for this notion. I’m confident I would not be able to pen a worthy addition, remake, rebuild or whatever for Evangelion for all my critiques. The tradeoff between 2.22 and 3.33 is between “competent but lacking” and “flawed but interesting”. Indeed, it’s easier to look back more fondly on the third entry now the series is over. Whether that’s because 3.0+1.01 retcons character motivations to make more sense is another matter. With how radical the shift is from the second to third, it would be fair to consider Rebuild to have two parts rather than four. I think there’s more value in considering each film individually, as each film is in dialogue with the last. Or, to put it less charitably, each movie is a course correction. Somewhere between the second and third plans drastically changed. Anno himself confessed that he could no longer understand Shinji’s feelings and related more to Gendo instead. Anno’s hesitancy would explain the delay and why the preview at the end of 2.22 is entirely inaccurate to the events of 3.33. Audiences can take the minimalism and overall short length either as intentional, finally laying the hammer down at the foundation of Evangelion, or that it’s a rushed mess, biding time for the final entry.

I would be more inclined to think it was some grand artistic statement if it did not also refuse to age up the eminently merchandisable girls of the franchise due to the aforementioned Curse of Eva. Shinji being a person out of time fits with being trapped within Unit 01, and I suppose there will always be more Rei clones. But inventing a Proper Noun Plot Device so that we can continue to be horny about a teenager is embarrassing. I assumed two of the most iconic characters in anime having a more dramatic redesign than “eyepatch” and “black plugsuit” would have fit more with this radical new vision for Evangelion, but that would have been a bridge too far. Blissfully the nightmare mid-apocalypse reduces the chance for product placement (at least until the iPhones and Suzuki cars in 3.0+1.01) but considering Anno’s goal to revitalise the anime industry, it’s perhaps unsurprising that some aspects still feel crassly commercial. But if you’ve seen any of the marketing, you’ll know that neither Asuka nor Rei are the focus; that role falls to Kaworu.

Kaworu left such an impact on the original series that it’s sometimes easy to forget he was only around for one episode, the episode before reality completely breaks apart. Twenty minutes is not particularly long to get to know a character, but he’s responsible for one of Evangelion’s most iconic and infamous moments, the descent into Terminal Dogma. While much is made of the lingering still frame of Unit 01 holding Kaworu, it is also here that the final deception of Nerv is laid to bare. That the true identity of Lilith was a mystery even to 17th Angel reframes the struggles of the rest of his species and makes his untimely death feel all the more pointless. Kaworu’s head falling to the feet of Lilith accompanies the complete shattering of Shinji’s psyche. To have a person reach out to him, care for him unconditionally, and then annihilate him with his own hands proves too much to bear. Did Kaworu genuinely care for him, or was that merely his alien way of interfacing with a useful human, one who the Angels had seen inside the mind and adapted to? It would take into End of Evangelion to show the extent of the damage, rendering Shinji near catatonic. This is only part of why he is so well remembered, of course. Having a character as gay-coded as Kaworu in this series stood out at the time, and while the new Khara approved translation for Netflix tones this down, the tenderness present in his relationship with Shinji is still refreshing today. There is, of course, a lot of fan content that attempts to expand on this relationship. Previous official efforts to expand on his character led to him murdering a cat, so I approached 3.33’s expanded take on him with trepidation. I needn’t have worried, since aside from a lovingly animated piano duet with Shinji, what screentime he does have is shared with Rei Q, a character who has more in common with the kuudere stereotype her original incarnation spawned than anything else. His time is not efficiently used, serving only to repeat his tragic end in broad strokes.

This time, he directly convinces Shinji to go down with him in Evangelion 13, a dual piloted unit with later plot significance, but for now, it appears just like Unit 01 with more arms. He gains Shinji’s trust in part by showing him the remains of the world. Why Shinji doesn’t notice that Kaworu doesn’t have to wear a protective suit outside is another matter, but it’s more kindness than anyone else has shown him in the movie so far. He also removes the DSS Choker and puts it on his neck. Why he does this and why Shinji also doesn’t question it is when I started staring longingly at my empty bottle of soju. They descend to remove the Spears of Cassius and Longinus from the corpse of Lilith at the base of Terminal Dogma, which Kaworu believes can be used to undo the damage Shinji wrought upon the world. He realises that something is wrong. There are two Spear of Longinus impaled within Lilith, instead of one being the Spear of Cassius. Maybe the fact that they didn’t face any resistance from heavily-armed Nerv after stealing an Eva Unit might mean they’re playing into Gendo’s hands. Shinji ignores him, so driven to undo his actions. But as the subtitle spells out, you cannot redo- that is, Shinji can’t, but the writers can. Third (or is fourth?) impact begins again, only for Kaworu to attempt to stop it (like the ending of 2.22) and be decapitated (like the TV series) by the DSS Choker. One could be charitable and take this as a clever subversion of Kaworu’s arc, or that this is simply his fate, echoed through timelines, an instrument of Quickening for both Shinji and (unwittingly) Human Instrumentality. Or perhaps it’s a metacommentary- both Shinji’s attempt to undo and Kaworu’s attempt to redo are failures. The Impact continues, only to be stopped by still debated means. A combination of Shinji, Kaworu and Mari’s actions? 3.33 has no answers. It destroys the world of Evangelion, changes its aesthetic, throws in a dizzying amount of new concepts, but it falls back on the plot structure of episode 24. You cannot kill Evangelion. Perhaps it simply flowed through the staff. An inescapable spectre manifested in a whirlwind of pop-cultural touchstones, fan expectations and depression. They had merely destroyed its flesh. Not death and rebirth, but death and undeath.

Reading about Anno, he reminds me of George Lucas. Not just because of 3.33’s “rhyming” with past material, but both are as interested in telling a story as shepherding a franchise. The story of Lucas giving David Lynch a headache in talks over him taking over directing duties for Return of the Jedi is funny. Still, it reflects a man who perhaps wanted Star Wars to go on but was not wanting to be its auteur. His regrets about selling Star Wars to Disney makes me wonder if Anno feels similarly connected and disconnected to Evangelion. Rebuild and the Star Wars prequel trilogy both reflect on their directors as much as the army of people working on them. For perhaps a more flattering comparison, consider Hideo Kojima. He was similarly obsessed with the idea of passing his most important work to the next generation, all while holding onto Metal Gear Solid for dear life, intervening every time his juniors didn’t quite hit the mark. I’m sure if Kojima wasn’t torn away from his baby by his acrimonious split (the second in one essay!) with Konami, Death Stranding would have starred Gaseous Snake and his quest to use the Patriot’s network to reconnect America. Anno managed to take Evangelion with him. While he had some mild success with post-Evangelion projects (his Cutie Honey reboot is still pretty entertaining), I can understand wanting to do more in that space. The situation is too complicated to write off as a cash grab; an actual cash grab certainly wouldn’t have taken as long. It certainly wouldn’t have taken until the third film to have Eva Unit versus Eva Unit combat.

Evangelion ANIMA, a light novel series penned by Evangelion’s mech designer, has many things in common with Rebuild. It also acts as a sequel and another take on the original story, with the point of divergence being Asuka acting as the key to Third Impact, averting the apocalypse. If this sounds interesting to you, know that ANIMA is at best completely bananas and at worst absolute dogshit, a title I would have far less issue labelling a cash grab. I have many complaints about Asuka’s treatment in Rebuild, but I guess I feel better knowing that at least she didn’t fuse with Unit-02 and become some sort of giantess fetish robot that regresses to the mentality of a baby. A full breakdown of ANIMA, with all its Super Evangelions and magic classrooms, is, like the manga, far beyond the scope of this essay. Hopefully, though, this clarifies that for all my criticisms of Rebuild, it could be far, far worse. If the final entry had turned out to be terrible, there would still be something to salvage from the experiment. Thankfully, that isn’t the case. Despite being the work of four directors, the final film is the most personal of the tetralogy and goes to some lengths to justify the Rebuild project as a whole.

After an agonisingly long production (more on that later), the final product is, yet again, different from the original preview. I expected that much, the scorched earth approach of 3.33 left many possibilities, but pastoral Evangelion wasn’t on my list of guesses. It’s a welcome reprieve from the steel and concrete of NERV and WILLE, with Village 3 (based on Anno’s hometown) appearing almost utopian, if not for the strange headless Wanderers and the floating debris of Near Third Impact. Perhaps this is less surprising when we consider that in the time between the third and final entry, Anno starred in The Wind Rises, and it seems that time at Ghibli affected him deeply. It’s the first time Eva has considered nature beyond humanity, aside from maybe Shinji’s running away sequence. Kaji cares explicitly more about preserving the biodiversity of Earth’s lifeforms, knowing that Human Instrumentality discards individuality and declares humanity supreme, with no room for other beings. Admittedly the escalation from “I like growing watermelons” to “HUMANS ARE GARBAGE PROTECT ALL THE SPECIES” is more than a little silly, but it’s a welcome positivity. It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, but it’s nice that 3.0+1.01 allows for both. In 3.33, WILLE only exists as a paramilitary organisation, somewhere between Space Battleship Yamato and White Base, with it being somewhat unclear why any civilian would live aboard Wunder. 3.0+1.01, KREDIT, a WILLE affiliated organisation, works to support people suffering under the Near-Third Impact, closer to a mutual aid organisation than a charity. As long as you don’t try to consider the resources required to create them, the giant dandelion-esque arks floating above the Earth represent a kind of hopeful science fiction that is more comparable to Star Trek than Evangelion. It’s a stark change in tone, with the only reminder of 3.33’s darkness coming in the form of Shinji. He stumbles around in a catatonic state similar to End of Evangelion, only worse, somehow. He cannot communicate at all, puking at the sight of Asuka’s DSS Choker, refusing to eat. Shinji is at his lowest point, near suicidal. Kensuke and Touji return in this movie, but even they cannot pull him out of this fugue state. That falls to Rei Q.

The most compelling aspect of Rei Q is that while she is a clone of Rei, she is not considered by herself or others actually to be Rei Ayanami. 3.33 sets this up after Shinji fails to rouse what he believes to be the dormant Rei with books. Realising she is a different person, he refutes her presented identity. I assumed that would be the end of it, and yet this comment becomes the crux of her arc in 3.0+1.01. Hell, in official merchandise, she’s referred to as “Rei Ayanami (Tentative Name)”. She embarks upon a quest to craft her identity in the absence of one. Sheltered to the point of not knowing what a baby is (“Why did you shrink that human?”), she is the blank slate that Shinji craves for himself. Anno might want that too- indeed, she is the most successful iteration of Rei since her original incarnation, so naturally, she has to blow up. She meets with Shinji one last time, thanking him for granting her the name Rei, before dissolving into LCL, not long after discovering that she can’t live outside of NERV. There are worse examples of “fridging” (injuring or killing a female character to further a male character’s arc), especially since Shinji had already come out of his shell a bit. Still, with Rebuild having done its female cast so dirty, it would have been nice to have what amounts to a brand new member of the cast with a familiar face get her chance to shine, even if there was the possibility that they wouldn’t stick the landing.

.

.

3.0+1.01 is a house built on the collapsed remains of prior Rebuild films, both inside and outside the text. Signifiers of the previous movies (and occasionally the TV series) litter the landscape of the Near 3rd Impact, yet they are divorced from their original context. Likewise, the constant resetting and the tortured development means that it cannot expect all viewers to have rewatched (or even watched) 1.11 through 3.33. It’s hard for me to evaluate what the standalone experience would be like, but I’d imagine it would function decently well with a passing familiarity of Evangelion. In that sense, we could easily consider the first three to be failures, with only really 3.33 affecting the final release. But it only hits as hard as it does because of the entire history of Evangelion. Metal Gear Solid 4 is a tempting comparison, an incredibly ambitious but daft ending, held together by fanservice, counting on the weight of nostalgia to strike the final blow. You could technically play it in isolation and have a decent time, though you’d have to ignore the hundreds of references sailing over your head.

Similarly, if you wanted to make sense of all the Proper Nouns thrown around in this film, you’d lose your mind, but at only two and half hours compared to MGS4’s eighteen, it just about manages not to give the average viewer an aneurysm. That’s not the only reason it works, though- simply put, Evangelion has made more of a mark on popular culture. Alongside Mobile Suit Gundam, it’s one of the strangest media properties to become a franchise juggernaut. Much as I love Metal Gear, the likelihood of someone having played every game across multiple consoles is much lower than having watched Evangelion. A synthesis of everything Hideaki Anno liked and wanted to create, now that it has become an institution unto itself, both what influenced it and what it influences are folded into the broader conceptualisation of Evangelion. An unfortunate side effect is that with Evangelion eclipsing the popularity of what it references, many viewers will take it as the originator of these tropes. It’s not dissimilar to the work of Quentin Tarantino being more popular than the B-movies he lifts from- this isn’t an issue if we assume people will go back and enjoy those works, but this rarely occurs. It’s a shame because while sometimes having extensive genre knowledge can hurt your enjoyment of a project (the likes of Stranger Things and Fear Street are probably more enjoyable without the deja vu), understanding where Evangelion came from doesn’t detract from it.

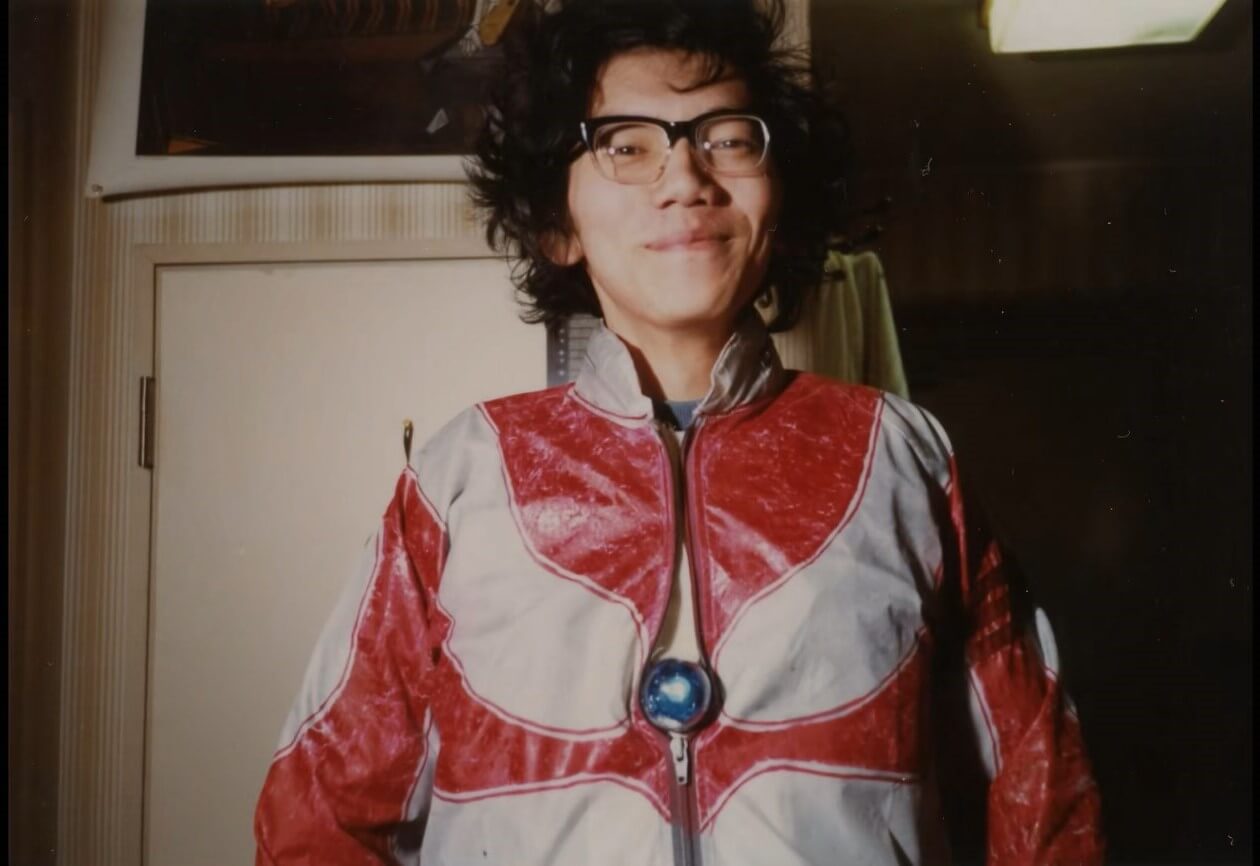

One of the most critical influences on Evangelion is Ultraman. The time limit on the Eva units, the Core in their chests resembling the Color Timers, the way they move like people in suits, even the Christian symbolism all find roots in the work of the Father of Tokusatsu, Eiji Tsubaraya. Anno is a massive fan, director and star of the fan film Return of Ultraman, made with proto-Gainax “studio” Daicon Films. Ultramen and the Ultra Beasts are present (alongside other uncountable otaku ephemera) in the legendary Daicon III and IV opening animations for Nihon SF Taikai, vital stepping stones in the formation of Gainax. Without Ultraman, there is no Evangelion, and Anno is unsure he would even have sought out this career had he not watched Ultraseven as a child. Before he goes full circle with Shin Ultraman, it’s nice to see the Eva units finally return to their tokusatsu roots in the final clash between Gendo and Shinji, clumsily bouncing cardboard buildings around a set. They fight within a so-called “minus space”, a reality shaped by human thought, accessed upon the awakening of Eva Unit 13. One could be cynical about the reuse of environments from the past Rebuild films were it not for the efforts to make them all slightly off. Wooden buildings launch with wobbly physics, giant Evas square off in the confines of a beer-strewn apartment, even the CG used in this sequence looks noticeably rougher. Though 3.0+1.01 mostly lacks some of the more weightless, dizzying fights of the previous, it’s undeniably cool to see Unit 01 get a last bit of spectacle before we go off the deep end.

After the film came out, a friend over Discord was curious to know my thoughts. They had seen the original series and End of Evangelion some years ago but didn’t have much of an interest in watching Rebuild. I did my best to try and explain the overall plot, but any screenshots I shared from the finale only inspired incredulity. It’s understandable- Evangelion Imaginary, in particular, is an even blunter and more meta moment than Fuyutski’s prior lament. Shinji, and therefore we, see it as “Black Lilith”, as humans are capable of believing equally in fantasy and reality, therefore our prior understanding of Evangelion colours all we see after it, a part of a prism of all we’ve experienced. A young Hideaki raised by television, crafting a career out of doujin work and an insatiable desire to create something that would stand alongside his childhood favourites, saw more benefit in fantasy than reality. His father, Takuya Anno, lost his leg in an accident, making it hard for Hideaki to leave the house as a child. Angry that another man’s mistake could take something so important away, he resented his fate, and that resentment would also reach the young Anno. This retreat into fantasy brought great success, but Evangelion Imaginary (and the ending as a whole) suggests some conflict there. From there, Rebuild’s first and only psychological breakdown occurs, including the infamous train carriage, though the focus is different: it’s on Gendo.

Even at the time of the original series, Hideaki was closer in age to Gendo than Shinji. Now in his sixties, it’s understandable that he would relate more to the older Ikari, and if anything, it’s surprising that he hasn’t had this degree of focus before. He has more walls to break through than Shinji; previously, it took the world reducing to LCL in End of Evangelion for him to express anything personally. This time, it only takes a Shinji who has gotten his shit together. Though Gendo has forsaken his humanity, he still produces an AT field when his son approaches him. The science of Evangelion is always more in service of drama than consistency. While the endless rambling about different spears and Gendo’s laser eye sent my eyes reeling, this low stakes and arguably cornier example works better for the visual abstraction making something more straightforward rather than more opaque. Gendo is alone, partly from trauma sustained at his father’s hand and from purposeful isolation. He regarded other people as a hassle, choosing to focus on piano and knowledge, activities free from pain and unpredictability. Gendo is an Otaku in the traditional sense, a true example of a “database animal” cramming knowledge into himself to avoid interfacing with the people around him. Yui offered a hand out of the darkness. Toshio Suzuki, a producer at Studio Ghibli, said Anno “wanted to become an adult, but he missed the boat”. The parallels between Yui and Moyoco Anno are not hard to see, and perhaps Hideaki wonders what would happen to him without her. I don’t wish to ride the line between media analysis and private life speculation anymore than I already have. Still, considering Hideaki would not have even eaten zucchini without extensive persuasion from his wife, she seems to have been a positive influence on him. Moyoco even appears in the film, holding their beloved cat. Does Hideaki think he would go on a similar path to Gendo with the absence of Moyoco? I don’t think even he could answer that.

The shadow of End of Evangelion looms large over the finale. Yui Ikari’s giant form explicitly evokes the Rei/Lilith hybrid, though somehow even more uncanny and unsettling. But every Rebuild movie has referenced End of Evangelion in some way. What makes this any different? Well, it’s another ending, of course, but it’s more interesting to discuss the thematic differences than debate which conclusion is more effective. Rei in EoE offered comfort to most before reducing them to LCL (except Gendo, but he probably deserved it), here that role falls to Shinji, except he restores rather than destroys. Asuka lost herself in the activation of Unit 13, existing now within a mind palace similar to the pocket worlds post-Third Impact. Giving Asuka Shikinami some interiority here is the definition of better late than never. Making her part of a clone series seems like a handwave to criticism of her being a more flat character in Rebuild, but what’s here is decently executed, if melancholy. Kensuke also gets some belated characterisation here, filling in as a father figure for Asuka. Again, both his and Toji’s relative absence in Rebuild hurts it as a standalone project. Still, I’d given up on considering Rebuild and the TV series as separate entities by this point. Shinji releases her from this prison of repeating memories, presumably thanks to his infinite synch rate. Gendo, too is saved, albeit temporarily. Kaworu realises that Shinji does not need him to be happy anymore and walks off into the yonder with Kaji, mysteriously connected to Kaworu’s mission. Here’s as close as you’ll get to confirmation of the sequel theory, that is the theory that would get you banned from EvaGeeks in prior years. Misato still gets blown up, but consider that only her, Kaworu and the tentatively named Rei Ayanami die out of the main cast. That’s a net improvement in positive vibes over End of Evangelion. That’d be a flippant but not incorrect summation of this ending- what if EoE was the product of a happier man?

![Rei Q and Shinji stand before the logo of Neon Genesis Evangelion, projected on a wall. Rei says “Birth of a new world. Neon Genesis”]

That’s not all there is to it, though. Shinji also meets with Rei- not the Rei who melted, but the one he saved at the end of 2.22. Her hair has grown out, and she’s holding a doll named after the baby her lookalike counterpart thought was a shrunken human. She’s in a soundstage mimicking the ones used by Khara for motion capture scenes, including cameras with DualShock 4’s attached for tracking. As Shinji explains to Rei that there’s a place for her in the world, a place without Evangelions, a projector begins to whir. He promises not to rewind or repeat as scenes from the TV series, End of Evangelion and Rebuild fast forward in the background. He will rewrite the world to be without Evangelions entirely. Perhaps this is Anno finally pushing out of his more extreme otaku tendencies, coming to the same conclusion Yoshiyuki Tomino, creator of Gundam, came to all those years ago. Mecha are rad, but they shouldn’t be. We shouldn’t forget what horrific destructive power they wield in the name of spectacle. An Evangelion is even more dangerous than a Gundam, yet neither should exist in this world nor should their real-world counterparts. Anno can’t quite shake his military otaku roots, with many characters named after Japanese battleships. Still, it’s a start, and considering that’s present in the works of Hayao Miyazaki as well, I’m willing to give him a little slack. I’m still undecided on whether the line “birth of a new world- Neon Genesis” is incredible or terrible, and I’ll probably oscillate between the two until the end of time. I’ve seen comparisons to Kingdom Hearts floating around, and I can’t entirely disagree. It has the same brazen sincerity of a Nomura production, an ending that doesn’t care if you find it cringeworthy. I guess the difference between those people and me is that I think Kingdom Hearts kicks ass, so hell yeah. I would rather have one of the most profitable media franchises on earth risk ridicule than wallow in safe selling mediocrity. Having a giant Yui come back to life to protect Shinji is pure emotional writing, but it works. Perhaps a little much is the implication that Gendo would reject his humanity and doom the world three times over to say goodbye to his wife. Rebuild makes Gendo its singular villain, a “just as planned” master manipulator by sidelining SEELE. In light of his confessions to Shinji, knowing that he finds people unpredictable, the cold manipulator schtick doesn’t work. Perhaps since achieving godhood, he can follow the script of fate, but that would rob the entire cast of agency.

Gendo isn’t the only one to suffer some strange characterisation choices. Fleshing out Misato’s rebellion against Nerv makes us question more why she ever worked for them, considering everything she knew. Asuka doesn’t wear a shirt in the majority of her scenes because of trauma, I guess. She also lives in a tiny room with Mari, so we can check the gay-baiting box before hurriedly pairing Mari with Shinji. That move is sure to piss off the maximum number of shippers, which, if intentional, is pretty funny. Kaji’s previously mentioned interest in saving Earth’s natural life makes WILLE a touch more coherent as an organisation, but little more. The less said about the reveal of Mari’s real name as Maria Iscariot (an obnoxious Christian reference even by Anno’s standards) and her incredibly stupid Unit 8+9+10+11+12, the better. It’s the significant deficiency in Rebuild that even 3.0+1.01’s nuclear option cannot remove. Evangelion has always had elements that work more in broad strokes, with conflicting details and convoluted terminology, but the character writing managed to hold it together. A two-and-a-half-hour movie simply does not have enough time to make up for all that lost ground, so 3.0+1.01 has to overcome it with a potent mix of emotion, surreal spectacle and sheer bravado. That it manages that at all is something of a miracle, and partly down to its very last sequence.

Whether it was all in his plans or not, with Gendo finally able to embrace Yui, the new Spear of Gaius impales each Eva Unit in turn, including ones that don’t even appear in this movie. Shinji says goodbye to all Evangelions and all (Neon Genesis) Evangelion. The red seas of EoE are finally gone. Shinji watches the waves alone. The animation breaks. The world without Evangelion begins. It resembles the real world, but of course, our world isn’t one without Evangelion. I don’t think Anno truly wants that, but perhaps he does want this to be the torch-passing moment. Khara is diversifying its output, so there’s some hope there. As someone who never cared for the side material (except for the incredible WonderSwan game, which lets you raise Angels like Tamagotchi), I’m more than happy to let Evangelion fade into the collective consciousness. There are inconsistencies and strange decisions, but that’s true of the entirety of Evangelion. While writing this (and rewatching the movie with the less than stellar dub) has taken a bit of the sheen off my first-time impressions, I’m still happy that this beautiful mess came to a satisfying close.

There’s another piece of media that I’ve alluded to that is important to discuss. To accompany the final film, NHK released a documentary, “The Final Challenge of Evangelion”. Filmed over six years, it gives some fascinating insight into the production, as well as the mind of Hideaki Anno himself. In the documentary, he seems aware that previous Rebuilds have not escaped the shadow of the original. His decision to delegate to other staff is born from wanting difference. But as a fellow staff member laments, “Anno wants to delegate everything. But he can’t. In the end, he redoes everything.” Anno isn’t satisfied with “good enough”, so though Khara staff had free reign to experiment, ideas were often shot down midway through implementation, resulting in a staggering amount of unused material. Such an approach seems wasteful and undoubtedly not efficient. This attitude butts up against Anno the businessman, who says he only agreed to do the documentary for sales. Even as personal as this documentary gets, it’s hard to discern what Evangelion means to Anno. I wouldn’t blame him for not caring anymore, but as I mentioned earlier, Rebuild isn’t a product of pure cynicism. The documentary simultaneously illuminates and obfuscates- I understand more of Hideaki but less of his intentions. This is somewhat deliberate- he repeatedly asks the film crew to focus less on him and more on the staff, insisting that their confused and frustrated faces will make for more exciting television. The relationship between documentary and reality has always been a tenuous one. Even sans editing, once you put a camera down, you have decided what to show and not show. Objective reality is impossible to capture on film, and Anno knows this, claiming that “Documentaries actually don’t exist. Only usable footage gets used. At that point, it becomes a fiction we call a ‘documentary’”. Anno complicates this relation, occasionally directing the documentary makers himself, in one instance asking them to film a storm outside for no apparent reason other than he felt it was a dramatic shot. Watching him rearrange the model of Village 3 over and over and over is hilarious and infuriating. Is the model even necessary? Is it worth sacrificing the sanity of your staff over the years to produce, well, anything? New hires are asked, “Do you love Evangelion? Make sure you still love Evangelion, no matter what happens, alright?”.

When I first finished this documentary, I was about half done with this essay. I had the sudden urge to pull my punches. Relating to Anno’s suicidal experiences made me want to be less mean. November 11th, 2011, almost ten years ago, I stared down from a two-storey stairway with the intention of throwing myself over. I’d spent weeks mindlessly trawling through archives of alt.suicide.holiday and an ebook of Final Exit- in a way, that’s what stopped me. I knew that I wouldn’t die. It would just hurt. I didn’t want to hurt. Neither did Anno- he says that’s all that prevented him from suicide after the ending of the TV series. I don’t know what it’s like to receive hundreds of death threats, have strangers on the internet fantasise about the perfect methods of murdering me. I don’t know if I could handle that strain even now. I don’t believe that experience made End of Evangelion a better movie- trauma can inform creative work, but the notion of suffering making great art is an overly romanticised one. Post End of Evangelion, Anno found himself in a creative slump, shopping around ideas to the likes of Studio Ghibli that, as he admits, all resembled Evangelion. EoE wasn’t as final nor cathartic as we might imagine. The End wasn’t the end, as it were. I’m glad Anno seems to be in a better place now, with the release of Shin Godzilla between 3.33 and 3.0+1.01 and the upcoming Shin Ultraman and Kamen Rider movies symbolising a new era for Anno. Perhaps he’s done with anime altogether, and that’d be just fine- Rebuild was the rebirth Evangelion needed to close that door finally.

Evangelion means a lot to me. Both it and I have taken a series of sharp, sudden changes rather than some gradual evolution. I don’t want to say this is endemic to everyone with depression- if there’s one thing I’ve learned, the word depression describes so many things that it’s a barely helpful word. It’s kind of a defence mechanism for me, guiding me into repetitive patterns before the next revolution. A scorching nightmare of a summer that won’t end forms the background of one of the lowest periods in my life. To chip away at this essay has taken the scraps of energy left in the wake of the crushing stress and monotony of work. The Dummy System took over, me as a pilot staring out behind my eyes, able to only exert the most minute will over my mind and body. Now that things are improving (albeit very slowly), I’m sitting here, trying to piece this together. Make some kind of conclusion. The pressure is off; the relevancy is fading. Some other online persona may have already served you a retrospective, analysis, video essay in the wake of the final film. I’ve never been good with deadlines. The only pressure now is to have some kind of “wham” final passage, a bit that’ll make you consider linking or retweeting this. This essay has become so intertwined with a miserable time that I can no longer evaluate it. I’ve gone back and forth, labelling this an essay, a critique, a retrospective- it’s a bit messy to be any one of those things. This took a lot longer than expected, has had significant parts changed and changed back. I’ve had twenty-something tabs open in Chrome for weeks now. I wasn’t even really clear what my purpose in writing this was. Kind of perfect for Evangelion, right?

“Maybe it would be better if Evangelion didn’t end” is a sentiment that hangs over the documentary. Maybe it would be better if this essay didn’t end, too. A final stop is something you can’t take back. Anno had to reboot the series just to stop it again. This won’t be the end of my thoughts on Evangelion. But it is a line in the sand. After this point, Anno can move on. Maybe I can too.

..