ANATOMY OF AN ASIAN VAMPIRE

You cup your hands over your mouth, nails piercing your cheeks, trying to force your breath back into your lungs. It’s in the house. You can’t see it through the crack in the wardrobe. But you know it’s there. You can hear it. Heavy thumps on the hardwood floor at a regular, unnerving rhythm. You can feel it. Swirls of frozen, suffocating air. Don’t breathe in. Don’t let that survival mechanism kill you.

The thumping stops. A shadow between the wardrobe doors. You creep back, back into moth-eaten robes, as if those few centimetres of distance will save you. But they won’t. The ice has pierced your heart, and at that moment, your body betrays you.

You breathe in.

A clawed hand smashes through the door and tears it from its hinges. You try to scream, but you can’t make a sound. The air is sucked out of the room. It is upon you now. A face pale and sunken stares into your soul, the only sign of life the blood dripping from its fangs. Arms of forgotten dynasties embrace and draw you in, and in your last moments, you finally see-

Oh. What is that, even? A vampire? A zombie? Both, and yet neither. Jiangshi, literally “stiff corpse”, are hopping contradictions, often referred to as “Chinese vampires” despite lacking almost any of the characteristics of their European cousins. You’ve probably come across them, even if you didn’t know it. My introduction to them was in Super Mario Land, Mario’s first proper (if charmingly bizarre) portable outing. Inhabiting the Chinese-themed Chai Kingdom, I might not have known what they were, but I sure recognised the “Oriental riff” in the background music. You know the one, that nine-note melody that’s in pop songs like “Kung Fu Fighting” and “Turning Japanese”, one that’s almost two hundred years old and, no surprise, of Western origin. But it’s come to represent China, or at least how the western world views it, and it was enough to connect this tiny hopping sprite to some vague idea of Asia in the soup of my pre-adolescent brain. At least, it was enough context that Darkstalker’s Hsien-Ko didn’t confuse me much. But I didn’t think either were vampires or zombies, just some other kind of monster I hadn’t seen much of before. So why are they confused for both?

First, let’s work out what makes a jiangshi distinct. They’re “stiff corpses”, and so with legs and arms in rigour mortis, they are only able to hop. They most often wear the uniform of a Qing official, a mandarin, with a talisman attached to their round top hat. The purpose of the talisman varies, sometimes freezing them in place, sometimes controlling their movements entirely. The latter relates to their founding myth, that families would hire Taoists to reanimate the corpses of faraway relatives, who would then hop all the way home (“transporting a corpse over a thousand li (around 500km), “千里行尸”). There’s also the more believable story of corpses were sometimes transported upright, particularly in Xiangxi (“湘西赶尸” literally “driving corpses in Xiangxi”), the bobbing up and down on bamboo resembling a hop, but I’m going to stick with the way cooler answer.

They don’t (usually) drink blood, but they do kill to absorb qi from their victims. If you want to avoid their wrath, you must hold your breath. What about the similarities? Well, they’re reanimated corpses and not particularly smart ones at that, and their arms-out pose is not that different from your stereotypical Romero zombie. This is why when you look up the word zombie in most English-Chinese dictionaries, you get jiangshi, and more importantly, if you ask for a jiangshi in a Chinese bar, you’ll get a zombie. The vampire similarities go a little deeper- sure, your average vampire is smarter and hotter, but there’s more than a whiff of Count Orlok to the scarier depictions of jiangshi, nevermind that they live in coffins and cannot go out during the day. More importantly, with their Qing-era robes, they represent a similar rotting aristocracy. However, while vampires often keep in step with the fashions of the time, jiangshi do not, depicting a past dynasty seeking revenge on the present. Yet despite the more significant similarities, vampires are entirely distinct in Chinese, known as “吸血鬼” (lit: blood-sucking spirit).

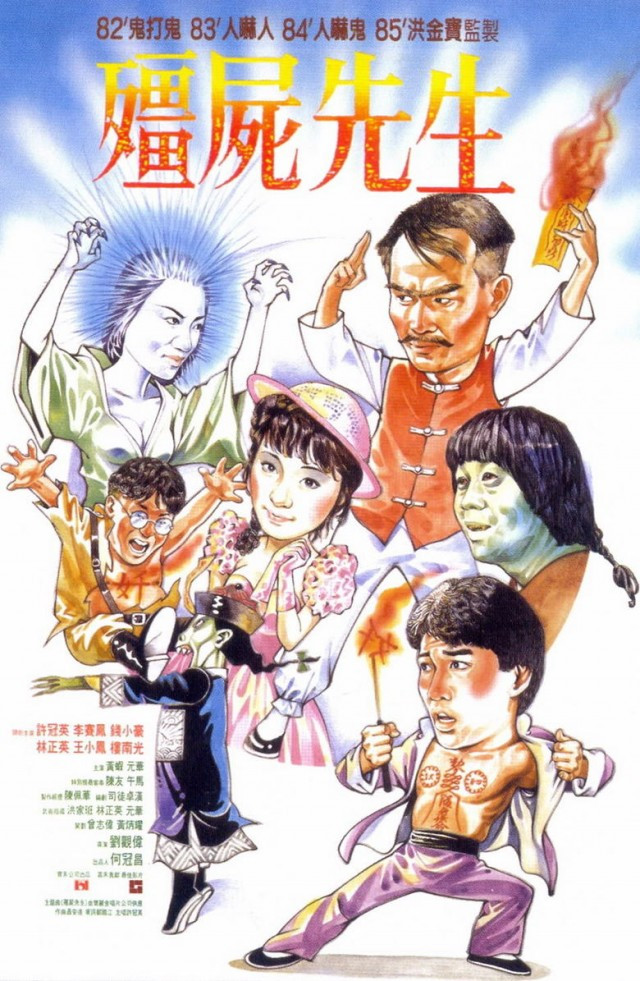

Ah, but then there’s this movie:

Mr Vampire wasn’t the first jiangshi movie, nor the first Hong Kong horror comedy, but it provides the archetype for both. The plot is straightforward- a Taoist priest is tasked with digging up and reburying a wealthy man’s father in a more auspicious location, but surprise! Turns out he’s a jiangshi. It’s a relatively tame but entertaining movie (weird horny ghost bit aside), perfect Halloween fare. What’s interesting is how it presents and sometimes adds to the jiangshi lore. The prime defence against them remains to hold your breath and apply controlling talismans to their foreheads. Though I’ve found some unconfirmed reports of glutinous rice thrown around during funerals to absorb evil spirits, using it as medicine and a weapon against jiangshi appears to be a Mr Vampire invention. Spreading the curse like some kind of jiangshi virus via bites and other wounds also became a genre staple. This film was so successful and influential that any such addition was immediately canonised. It’s easy to see these additions as merely adding vampire and zombie tropes. While that is both kind of true and kind of disappointing, I have to acknowledge that they’re clever spins, and selective enough that the jiangshi itself isn’t drowned under comparisons.

Clearly, it worked, and beyond even the financial success, you don’t need to look far to see its impact. Judging by the reactions I’ve gotten from mentioning it to my Chinese friends, it’s a typical first horror movie, one responsible for many childhood nightmares. A reputation that reminds me a bit of Gremlins or other so-called “gateway horror”, striking imagery and gore couched in comedy that neuters the scares for an adult but lures kids into a false sense of security. Rigor Mortis reunited several of the cast members from Mr Vampire for a more self-serious outing in 2013. You’ve certainly made a mark if you get the dubious honour of a maudlin nostalgic spiritual successor. But that’s the problem- it’s a film so lightning in a bottle that it’s codified an entire genre, so much so that even one of the very few serious pop-culture takes on jiangshi is inextricable from a horror-comedy that is much more comedy than horror, kind of like if we forgot how to make scary ghost movies post Ghostbusters.

But yes, that English title. In Chinese, it’s known as “僵尸先生”, or Mr Jiangshi, and since we’ve established that jiangshi is more often translated into “zombie”, why Mr. Vampire and not Mr. Zombie? The answer appears to be mere marketing. There have been Hong Kong vampire movies for far longer than jiangshi movies. Titling it Mr Vampire undoubtedly helped it succeed globally, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it helped in Hong Kong, too. I suspect it being a solo monster also influenced the decision- one zombie isn’t particularly scary. You need a horde. A solo vampire commands a presence all of its own.

So how about if we had seven of them? Enter Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires, a co-production between British horror studio Hammer and Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers Studio, most famous for their martial arts movies. So naturally, it’s a martial arts horror movie. The pairing isn’t as strange as it might seem. Shaw had released several horror movies before Seven Golden Vampires and would continue to after its release. The latter wasn’t the case for Hammer- this was their final Dracula movie, and while its dire financial performance wasn’t the only reason for their death, it was another nail in the coffin. Or, a stake through the heart, if you will. And well, uh, even if you won’t, it’s worth examining how this final Hammer Dracula film adapts the vampire myth.

The titular Seven Golden Vampires rule a rural Chinese village, but their power is fading. Their leader, Kah, seeks the help of Dracula, who is imprisoned within his castle. Kah gets the help he seeks, but not in the way he sought it- Dracula takes over his body, seeking to rule over a new flock in China. When I was first watching the film, I assumed this plot point was a way to dodge having to fly out Hammer’s actors to Hong Kong, but then the very next scene has Van Helsing (Peter Cushing) teaching in a Chongqing University (then Chungking, but we’ll have quite enough of that romanisation later). I was still suspicious- it takes a long time for Peter to appear in any shots with the Chinese cast, to the point where I wondered if they were on separate sets. But no, they fully committed to the bit, including, yes, Van Helsing martial arts. He’s here chasing that same legend of the Seven Golden Vampires, which is the subject of his lecture. He tells the story of a farmer who fought the vampires, which reveals two weaknesses. One- their power lies in an amulet hung around their necks. Removing it leaves them vulnerable but is not enough to slay them. Two- they fear Buddhist imagery as much as a European vampire would fear Christian. The farmer places the stolen amulet next to a jade Buddha statue, which sets one of the seven ablaze when trying to retrieve it. Cutting seven down to six before the plot starts feels a bit cheap, but it serves its purpose. It’s less elegant than Mr Vampire’s melding of western and Chinese horror lore, though it still poses interesting questions. In removing the need for religious weapons to be Christian in origin, it recontextualises the crucifix from a symbol of the one true god against devilry to a symbol that draws its power from the faith of the user and the fear from the vampire. To me, this doesn’t devalue it but rather personalises the meaning of these symbols and universalises the struggle between good and evil beyond Christendom. It’s probably not that deep. After all, the amulet (and their dress in general) is a rather lazy and barely explored attempt to distinguish them, as is the bizarre sacrifice pool the village girls have their blood drained into. That any thought went into this crossover is surprising enough, and while I don’t think it does enough to keep the vampires threatening, it’s still a pretty fun movie. B-movies are always a gamble of whether or not the outrageous premise will be matched by the film itself, and it gets close enough for a recommendation, albeit to a very specific audience (you’ll know already if thats you).

Why does it matter, anyway? Well, it doesn’t much, I suppose, but as you might have guessed, I really like jiangshi, and I think they deserve more than the euro-centrism implicit in “Chinese Vampires”. Mr Vampire and Seven Golden Vampires seem opposite in their approaches, but Dracula’s influence looms large, even in the movie he’s not in. I’m not sure if the marrying of jiangshi and vampire can be undone. Is that a bad thing? While I love the collective mythologies of the classic Universal Monsters, it’d be nice if jiangshi could be viewed outside that century-old grouping, especially since jiangshi as folklore stretches way further back. Literature might offer more serious takes, but while I can speak and read some Chinese, entire novels are a bit out of my reach. There’s been a lot of talk regarding the death of Chinese ghost stories, and while I think reports of its death have been greatly exaggerated, it’d certainly help if one of China’s best modern monsters could stand on its own. Or if not, it’d be nice for them to get better modern representation than endless gacha characters.

But hey. It could always be much worse.

Have you heard the good word of Vampire The Masquerade Bloodlines? The cult vampire RPG/title word salad takes some getting into, but it consumed my brain and conversation for weeks. The combat sucks, but it’s such an atmospheric world. The cult PC RPG was something I decided to try on a whim, since (aside from Elden Ring and Ultrakill) I’ve ended up playing a bunch of 00s PC games this year. Max Payne and FEAR more out of nostalgia, sure, but what pushed onto Bloodlines was that other adorable post-Y2K vampire game, BloodRayne. I already wrote a whole article about it , so I won’t gush anymore about this extremely five out of ten video game, but this review of its sequel did strike me:

“A hugely enjoyable, polished action adventure with buckets and buckets of OTT gore. If you thought “Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines” too cerebral, its slasher B-movie blood relative could HAVE MORE BITE.”- CVG/PC ZONE, 2005

I promise I did not add that emphasis. The review is just that 2005. But more cerebral, huh? I’ve only played about an hour of Bloodrayne 2, but considering the plot feels like a sequel to a game that doesn’t exist, I don’t doubt that it could be more cerebral. I’d heard good things about Bloodlines for years. The infamous Ocean House Hotel level ended up on more than one of the strangely common TOP 10 SCARIEST MOMENTS IN NON-HORROR GAMES listicles, and I’d seen enough horny /v/ threads to know who Jeanette was. But it takes a lot to get me to play an RPG, even more so a cult PC RPG. The hours and hours of clan and build guides plastered over YouTube didn’t really assuage my fears that this would be One of Those Games, one with so many asterisks that it restricts itself to only the most dedicated. It is very much not that. Yes, the combat is pretty tedious, and no, it does not run great without mods (I had an easier time getting it running stably than New Vegas, for what it’s worth), but it’s a much more flexible game than those optimised build guides would have you believe. My build was no doubt inefficient, and I missed a whole quest that would have made getting blood a lot easier, but it’s not a particularly difficult game as long as you avoid the more gimmicky clans. It is “more cerebral” than Bloodrayne 1 or 2, but not in the sense of being more obtuse. Playing as Rayne didn’t sell the vampire (or even dhampir) experience since blood-drinking aside, she could be any one of the hundreds of post-Matrix leather-clad badasses that dominated early 00s pop culture. Bloodlines is slower, conversation-driven, and much more committed to the vampire theme. It’s really good, and I’ll probably have to write more about it in the future.

And yet. Chinatown.

Bloodlines is set in Los Angeles and separated into four main hub worlds- San Diego, Downtown, Hollywood and Chinatown. Bloodlines had a notoriously troubled development, and while I wouldn’t say it feels unfinished, the final hours are pretty undercooked, which doesn’t bode well for Chinatown. None of the quests in this hub are super interesting- not bad (except for the fortune teller back and forth), but they don’t play to the game’s strengths. That isn’t the real problem with Chinatown, though. The problem is that it’s pretty racist.

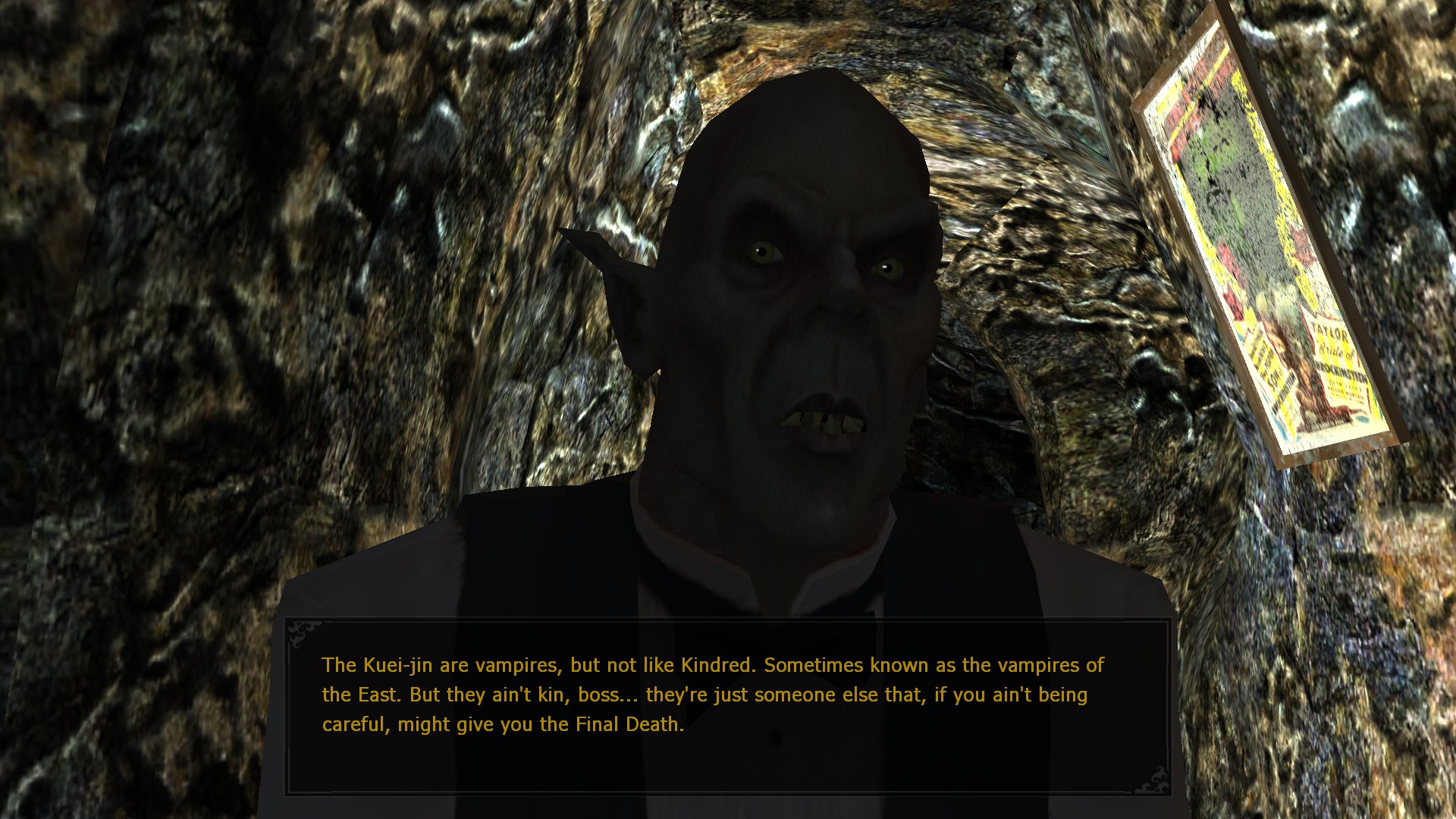

Such an accusation requires clarification. First, I should say that while I’ve lived in China for several years, I am white, and thus my experiences with anti-Asian racism have only been observed, not experienced. Secondly, the racism in Bloodlines is not entirely Troika game’s fault- they were working from White Wolf’s World of Darkness setting and were subject to pretty strict supervision to make sure the game represented the tabletop faithfully. This includes the “Kindred of the East”, the Asian (Asia in White Wolf’s material seldom refers to any South Asian country) vampires of the setting, known as the Kuei-jin. Let’s start with that name. This article on Ars Marginal goes into far greater detail on the many terrible things about that name. It is worth reading to gain further insight on the myriad embarrassments of the Kindred of the East sourcebook, but in brief, the name makes no sense. Kuei (鬼) is the Chinese word for ghost, rendered in the archaic Wade-Giles romanisation instead of pinyin, and jin (人) is the Japanese word for person. This bizarre combination of languages is supposed to imply a unity of Asian vampiric identity, at least as far as the “Middle Kingdom” (which White Wolf used to refer to all of Asia) goes. The problem (well, one of the many problems) is that these characters are used in both languages, making it impossible to discern from reading that it’s supposed to be two languages combined. Bloodlines offers another term, Cathayan, as an in-universe slur derived from the old European name for China, Cathay. This is not the justification given in the sourcebook, suggesting some degree of self-awareness/embarrassment on Troika’s part. Regardless, both Kuei-jin and Cathayan are bizarre and flattening as terms in a way that reminds me of Harry Potter’s Mahoutokoro, a similar nonsense term (“magic place”, a lazy name written with bad grammar and a pronunciation guide that is entirely incorrect) for the “smallest student body of the eleven great wizarding schools”, despite serving the entirety of Asia. I’ll give White Wolf credit- the Kuei-jin are less lazy than that, given that they have more than a blog posts worth of lore. It’s in those details where things go awry…

What makes a Kuei-Jin different from a “regular” vampire? Basically everything, save for that they consume blood and hate sunlight. Blood is consumed for Chi (Wade-Giles strikes again, but note the similarity to jiangshi) and “particularly enlightened Kuei-jin can occasionally tap directly into cosmic streams of Chi, without resorting to the carrion-eating and blood-drinking ways of their lower fellows” (KotE, pg 22). A Kuei-jin is not made, they are born and cannot sire fledglings or ghouls. They are both subject to and outside of samsara; the eternal cycle of death and rebirth continues, yet they are immortal. Like with the Cainites (WoD’s “western” vampires, descended from the biblical Cain but spelled Caine in game because???), this is viewed both as a strength and a curse depending on the sect, though the curse aspect is more emphasised given that enlightenment offers a release that is impossible for a Cainite. If you have any familiarity with Buddhism, Hinduism or other Indian religions, you may be experiencing a slight aneurysm at how White Wolf decided to “interpret” these concepts, but you should also note that they use Dharma as a class system, with one known as the Scorpion Eaters that started because the bomb on Nagasaki spread Tainted Chi and oh no I’ve gone cross-eyed. Considering the World of Darkness is populated with all manner of supernatural beings, I don’t mind them having their own mythology, and in removing the “conversion” aspect of vampires, there are other interesting questions to ponder.

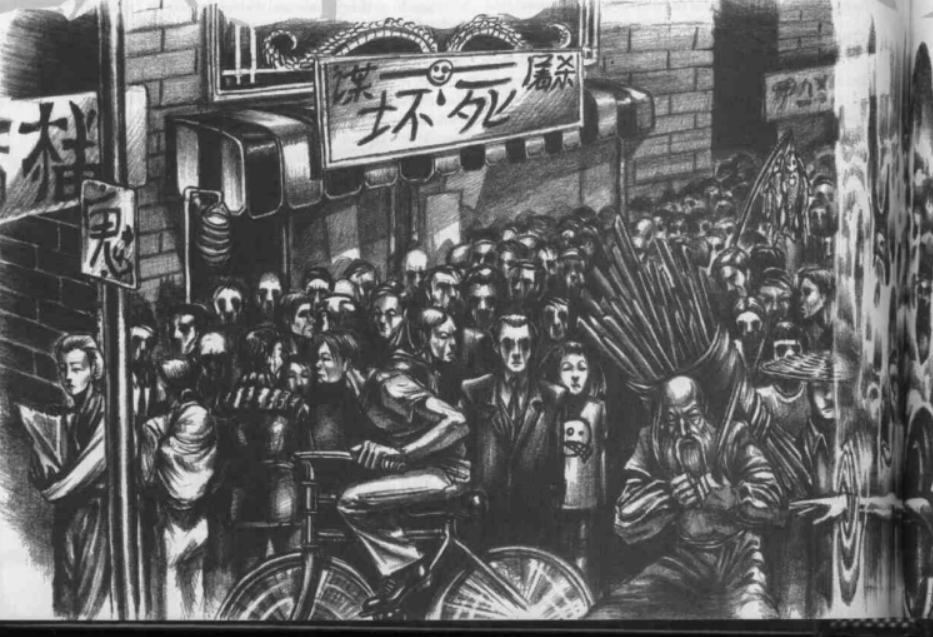

It has less unfortunate implications than White Wolf’s similar “better late than never oh god never mind” sourcebook for the “Kindred of the Ebony Kingdom”, the vampires of Africa. These vampires are implied to have come from Europe, given that their clans (renamed legacies here because god this needed more complicated terminology) are much the same but with different names, which also goes for one of their gods named Cagn, purposefully similar to Caine. This has the unfortunate further implication of casting their founding myths as misreads of the “correct” Christian-European ones, and that in character creation, a so-called Laibon (another pretty dodgily chosen name) is one generation further away from Caine and therefore has more “diluted blood” and may, in fact, be a sign of the coming apocalypse (Gehenna). A full dive into that book is out of the scope of this essay and my sanity, especially with gems like “In recent history, stone buildings have replaced much of the jungles, but the kine still display a ferociousness to rival the animals.” So perhaps it’s wiser for the Kuei-jin to be another supernatural race entirely. Or it would be if that separation wasn’t wholly predicated on them as an Orientalist other- they are more mystical (“their enigmatic behaviour and foreign mindset leave many Western Kindred ill at ease”, as one Bloodlines loading screen puts it), colder (the characters of John Woo’s Hardboiled apparently “display the dispassionate callousness so common among the Kuei-jin” [KotE pg 17]), and are plotting to take over the western world.

The so-called “Great Leap Outward”, a very clever play on the CCP’s agrarian collectivisation and industrial campaign, describes a shadow-invasion of the west, in theory against the Cainnites, but also not really. The Quincunx (the Asian equivalent to the Camarilla, the conspiratorial organisation that maintains the vampire masquerade) seek to right the historical wrongs of the nuclear and firebombing of Japan, China’s “Century of Humiliation”, and the European colonisation of Asia. I’ve never really been a fan of incorporating real-life atrocities into fantasy settings; however, these are large enough events that would be suspicious if absent. Their inclusion isn’t the issue. It’s what they’re used to justify:

“Hong Kong is the first step. The Quincunx has positioned soldiers and material all around the city ever since the transfer of power. Other outposts of Asian dominance in the West have seen the arrival of a few advance parties of Kuei-jin, concentrating themselves in the Chinatowns of New York, Boston, San Francisco and elsewhere. The free city of Vancouver, currently held in truce by the region’s Kindred and Lupines, has seen an increase in the activity of the Bishamon, who maintain a haven there. The insular nature of these microcosms provides the perfect cover for Kuei-jin to move undetected by Kindred or mortal forces. For the Quincunx, the question is not if, but when. Once the Flame Court is returned to Quincunx control, the Great Leap Outward is to commence. The Kindred have long wished to know the nature of the vampires of Asia. The Quincunx is determined that they will— and they will wish they never had never heard of the Kuei-jin.”

If “secret invasion through Chinatowns” is sounding alarm bells, it’s because of its notable similarity to the “Yellow Peril”, a conspiratorial racist metaphor that describes the apparent existential threat of Asia against the West. The idea was popularised by Thomas Pynchon protagonist reject Lothrop Stoddard and his book “The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy” from 1920. If you’ve heard it before, it’s probably because it gets a namecheck from Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby, and while I’m not going subject you or myself to any of the actual material, here’s how The Paper of Record decided to review it at the time:

“Lothrop Stoddard evokes a new peril, that of an eventual submersion beneath vast waves of yellow men, brown men, black men and red men, whom the Nordics have hitherto dominated . . . with Bolshevism menacing us on the one hand and race extinction through warfare on the other, many people are not unlikely to give [Stoddard’s book] respectful consideration.”

Well, perhaps the similarity is pure coincidence. Maybe the writers simply didn’t know what they were evoking. Except no, wait, they definitely do because they have the nerve to mention the Yellow Peril as an idea in the utterly bewildering recommended watching/reading section.

“Year of the Dragon— (U.S.) “Year of the Yellow Peril” is more like it. Still, this hyperviolent run through Chinatown captures the cynical world of the Kuei-jin better than many other less atmospheric efforts.”

Sidenote, what was in the water in the 90s? The whole sourcebook leans into anime as an aesthetic. I can only assume that the western anime boom was why they finally paid attention to Asia in the first place. Still, every recommendation in that part is either oddly contemptuous (“Vampire Hunter D— (Japanese) Yeah, yeah, the vampires in question are more like Kindred than Kuei-jin, the animation is less fluid than, say, Akira, and the moves are pure manga, but what the hell— this is a great flick and well worth the rental price”), or just really, really dumb (“Chungking Express — (Chinese) Sexy and cynical, this vivid tale portrays the desperation of modern-day loser on a crash course. Great visuals and atmosphere override a thin, confusing plot”), Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised when it recommends you learn about Taoism from “The Tao of Pooh”, as in the cartoon bear.

Now that’s off my chest, I want to preempt an argument here that the Kuei-jin are supernatural beings, not mortals, so White Wolf is not being racist; they are merely creating monsters. After all, it’s the World of Darkness. Believe me, I would like to think so. I really, really liked Bloodlines, and it would be nice if it wasn’t tainted with this. But that argument would only hold water if they hadn’t piled every single cliche and stereotype about Asia (again, not Southern Asia, they don’t get to come to the party) into the Kuei-jin and if that same treatment was given to the Cainites, but that simply isn’t the reality. Cainites are allowed to be of the cultures they’re born from, not some bizarre amalgam of entirely different countries. In each excruciating detail, it only becomes worse. Mortal Kombat is also full of orientalist nonsense, but it’s more believably just 90s dudes trying to make something cool because it lacks bewildering details. I’m not sure how much better that makes it, but at least it’s easier to handwave or reinterpret. The Kindred of the East sourcebook is genuinely the worst thing I’ve ever had to read for any kind of writing, not even just in the ways I’ve mentioned! There are also the horrible caricature drawings and 2edgy4you horseshit like Kuei-jin taking advantage of the one-child policy to eat excess babies and unclassifiable asides about Mao’s wife Jiang Qing being a fox spirit who lives in the mausoleum and christ I never want to see this fucking book again in my entire goddamn life.

It’s easy to see the orientalism of Bloodlines as mild in comparison. It’s less full-throated, for sure. You can also see a bit of a course correction in White Wolf’s books. The Kuei-jin Companion (still filled with some, uh, choice details) makes a bit more effort to try and honestly describe Asian religions and culture beyond sinister rituals and lawless wastelands of gang violence. With the benefit of several years after even this book, Bloodlines is for sure less eyebrow-raising.

Less. When you arrive in Chinatown, the first thing you’ll hear is broken English (spoken by a majority white cast naturally) and clucking chickens. You’ll pass Kamikazi Zen, a name that had my eyes rolling out of my sockets. You don’t actually get to get in there unless you complete a chain of side quests, and you can find an email that points out how silly the name is. Ok. It’s a joke. But it doesn’t have a punchline. There’s one line in the sourcebook that seems hastily added in a similar way “Kuei-jin itself is a recent and somewhat laughable polyglot designed to instil harmony between the Chinese Quincunx and the Japanese uji” (KoTE pg 13) because if you point out that it’s silly it stops being silly.

You might talk to the fortune teller:

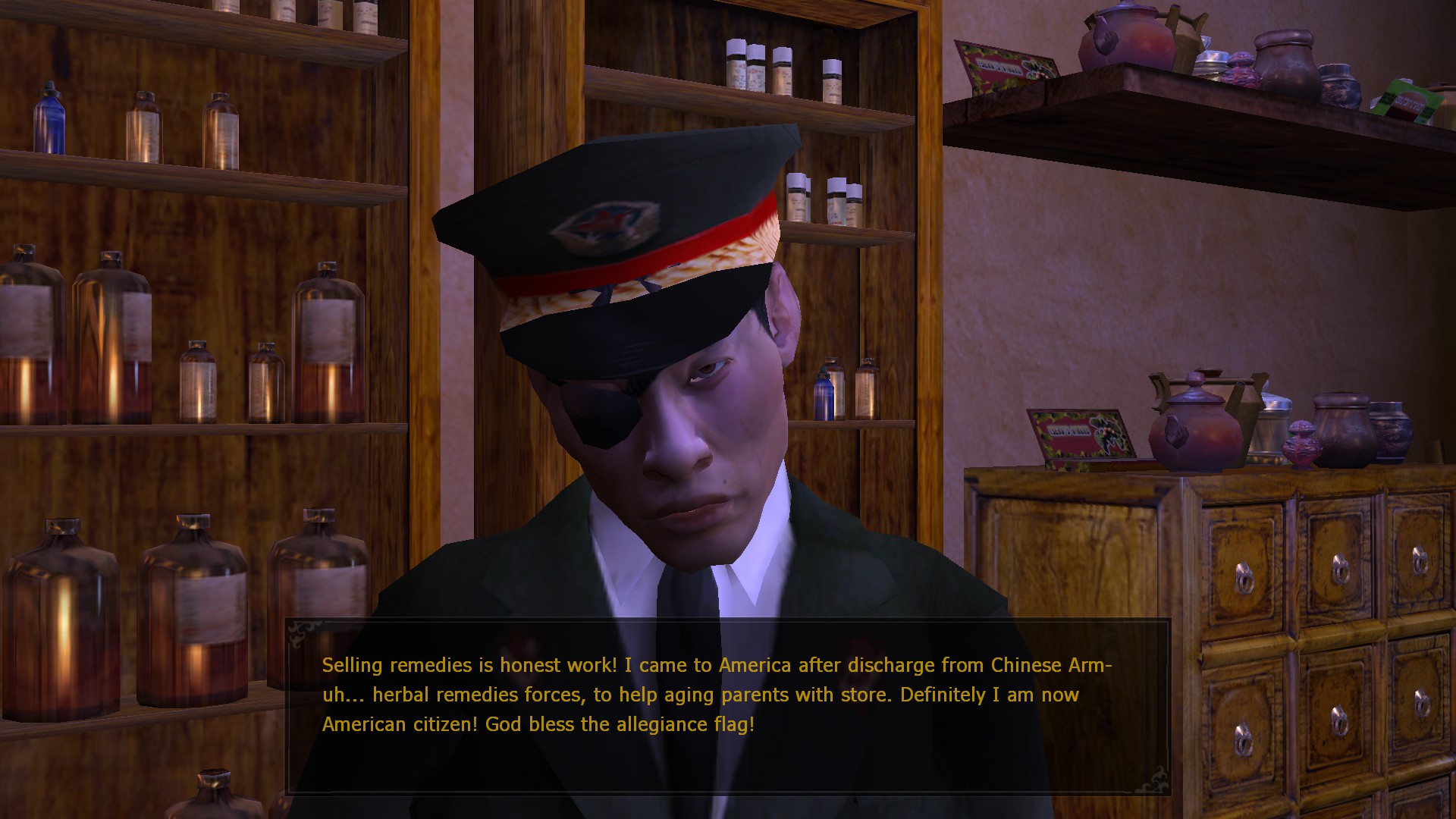

Or the ex-PLA weapon dealer, who will sell you a katana, naturally:

Both are voiced exactly how you might expect. But alright, those are minor NPCs. Ming Zhao rules over Chinatown, and while still voiced by a white woman and a bit of a “dragon lady” stereotype, she at least speaks in complete sentences without some Mickey Rooney-tier accent. This is where the game won me back over a bit- the other vampires you meet, even sympathetic ones, are racist to her and the other Kuei-jin, and the suspicions are laid on so thick that I was sure the game was going to subvert them. It, uh, doesn’t, since it turns out she’s an evil-shapeshifter jockeying for control of the entirety of Los Angeles, with her boss form being a tentacle monster, so actually, all the racist characters were correct. It’s frustrating because even this is far better than where we started. There’s more where this comes from, with the mortal fascinated with vampires calling himself the Mandarin while he speaks from the shadows on a TV, to a sidequest I thankfully missed with the Japanese character Yukie, who you can ask if she’s underaged because lord knows we weren’t going to escape that kind of shite either.

So, where does that leave us? Both the sourcebook and Bloodlines are near ancient history in this accelerated world. You can find a lot of similar problematic stuff in and around their releases. It was, as they say, A Different Time. Bloodlines 2, a game that will definitely come out honest for real, promises to make alterations to the Malkavian clan, so they aren’t just a collection of horrible stereotypes of mental illness. The Kuei-jin will not get such an update. They’ve effectively been memory-holed, their mechanics having to be jury-rigged into working with current editions of the Vampire table-top. The sourcebook and companion are out of print. So why even critique them? Well, because there’s nothing else. As flawed as they are, I’ve found many Asian players online who enjoy them as representation. I can’t speak to that myself, but I imagine it’s like how some of my fellows enjoy Sleepaway Camp, a kind of reclamation of something hateful. I don’t know if the Kuei-jin are hateful in the same way. I feel like that’s beyond what I can label. Maybe I want to give them points for trying, even if it was in a profoundly thoughtless way. But that might just be giving them the benefit of the doubt for the sake of my own comfort. I find their removal upsetting because they didn’t even try to do right by them, or if there was no way to do that, create something new in their place. Because in terms of pop culture, as “Asian vampires”, we have them, or we have jiangshi, which might not even be helpful to classify as such, and currently exist as either comedic slapstick or horny anime girls.

This article was planned to be released alongside a short story I’m working on, which is indeed about a vampire in Hong Kong. It isn’t finished, and the deeper I’ve got into this, the less sure I was about the pairing. It was supposed to be putting my money where my mouth is, a balance to all the complaining. But I don’t want it to seem like I think my story is a definitive solution, nor is it my place to attempt. I won’t can the story, but this has been illuminating, for better and worse. Another nail in the “stop writing so much about pop culture” coffin because I’m sure there’s better stuff out there. I just need to look for it, passed algorithmic Twitter recommendations and PC game nostalgia. This is the angriest I’ve ever made myself writing something, and a friend has just asked me on Discord why I’m even bothering. I could only answer that I wanted to finish it. This article’s title was inspired by my favourite title for any work of literature -“The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up” by Robert Burton. It has stuck in my mind because of that ending- opened, and cut up. My subjects in this essay have been opened and cut up, and now I’m staring at the pieces. But they won’t stay dead. In forms new and old, they’ll come back.

I await their deathly embrace.

..